As much as it is ridiculed in the wider public, political correctness is clearly still a concept that Germany cannot ignore. The debate currently raging in the German media (national and international, TV, radio, print and social media) about the removal of the N-word from children’s books is testament to this fact. White [1] cultural producers react emotionally to any perceived threat to their “artistic freedom” and, in their fury, give little consideration to the opinions, knowledge and expertise of those of us who have experienced living in Germany as young Black people; those of us who are raising and educating Black children in this country; those of us who are anti-racism activists; or those of us who have made a profession in the field of anti-discrimination. Indeed, while observing their curious behaviour, the words of May Ayim come to mind:

…alle worte in den mund nehmen

egal wo sie herkommen

und sie überall fallen lassen

ganz gleich wen es

trifft… [2]

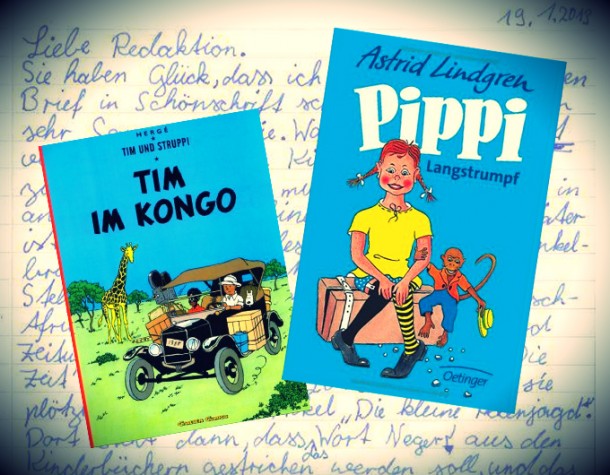

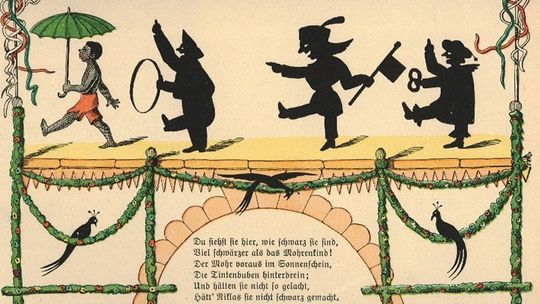

White cultural producers are fighting to retain their privileges: to date they still occupy dominant positions in the German art industry and therefore presumably experience the mere existence of political correctness as a threat. White cultural producers typically consider their own artistic productions to be of universal relevance and importance (and in consequence, the art of marginalized groups is considered to be less relevant for the white German population). These cultural producers are usually completely unaware of their own whiteness and of the constraints this will have on their perspectives, their creative work, as well as on their (potential) audience. For example, white German theatre practitioners who wish to explore themes of integration, immigration and discrimination through their artistic productions do not call on the wisdom of Black feminists, but instead choose to continue employing tired, outdated and often offensive stereotypes in a weak attempt to provoke and challenge the society within which they themselves have such a comfortable position. And most ironically of all, when these same theatre practitioners are challenged concerning their poor practice, they rarely seize the moment as a learning opportunity to reflect upon their own discriminatory practices but instead deny the credibility of their critics with a vehemence that belies the neutrality they claim to possess (see Otoo 2012). Political correctness is for them, at best, a pesky inconvenience – and at worst? As of this moment, most white Germans who comment on the removal of the N-word from children’s literature speak in melodramatic terms of the prevalence of censorship, the threat of 1984 scenarios and the death of artistic freedom. One pundit even resorted to using blackface to make his point [3]. It is as if these white Germans only grudgingly accept the existence of Black people in Germany, apparently believing the development of Germany into a (visibly) migratory society to be only a recent phenomenon (forgetting or repressing any knowledge of Germany’s violent colonial history), and therefore – so the assumption goes – these new Black populations fundamentally misunderstand what German culture is.

Of course, the role that we Black artists and artists of color have played in positively shaping German culture is well documented: Black people have lived and created on German soil longer than Germany itself has existed. In 18th century Europe for example, it was not uncommon for noble houses to have African musicians and it is known that in 1713, Frederick William I, later king of Prussia, asked for “several black boys aged between 13 and 15, all well-shaped” to be trained as musicians for his military regiments [4]. Additionally we know of Black German artists like Fasia Jansen (singer, songwriter) and Theodor Wonja Michael (actor) who survived Germany during the Second World War. Jansen, inspired by Josephine Baker, had always wanted to be a dancer but was forbidden to attend dance classes in the early 1940s as these were open only to Aryans. Wonja Michael worked as young man in the film industry, also in the early 1940s, serving as the African backdrop to images of white supremacy. One wonders: what more could they have achieved if they had not been limited to roles stipulated by the fascist Nazi regime? The research of Yvette Mutumba focusses on the situation of artists of African descent in present day Germany (see for example Mutumba 2012). Although they are not subjected to the explicity racist and life-threatening context of Nazi Germany, Mutumba explores how constructions of race still serve to shape the experience and work of Black artists in present-day Germany.

Some cultural producers are of the opinion that Black artists and artists of color should be granted entry into the German hegemonic art world for the simple reason of adhering to some politically correct guidelines. This thought process lends credibility to the belief that the current dominant structures are in fact the “norm” alongside which everything else should be aligned. However, the current structures are elitist and exploitative (for an in-depth discussion on this point, see Barrett 2012). They do not necessarily lead to the best art, they do not even necessarily lead to good art. Where white art is conceived of as “real” or “normal” and all “other” art is “deviant,” “ethnic” and by implication “not as good” a false division is created and perpetuated, with the result that white cultural producers retain their positions in a structurally racist art industry. Whether we want to or not, whether we are aware of it or not, we as Black artists working in predominantly white contexts deal with this constantly throughout our professional lives. We create in places where we are not seen or heard, where our mere existence is constantly denied or questioned by the majority of our fellow citizens; where we are not encouraged to learn about our history and where our history is devalued; where key parts – our parts – of humanity’s history is written out of the dominant narrative. For us as Black artists, creating in this context necessarily becomes a strategy, a practice of resistance, of what bell hooks coined “talking back” (hooks 1999). Art therefore is not for the elite, but for fugitives (Ajalon 2012): we use art as a survival skill.

The question therefore is not how can we as Black artists break into an elitist field, and thus inadvertently support white illusions of grandeur, but instead how can we – all of us collectively – imagine a whole new space, which does not rely on dichotomies of “in” and “out” but would be truly “inclusive” in the broadest sense of the word? A space where our roles as Black artists would not be to merely highlight inadequacies in white art, but to be an integral, essential part of a visionary whole? What could happen, for example, if hegemonic cultural producers would promote the roles of Black poets as societal commentators? In his poem “Defending Dessau,” spoken word artist Philipp Khabo Koepsell writes about the death of Oury Jalloh, a Senegalese man who died in mysterious circumstances in a German police station in 2005 [5]:

an african man

burned to a flake and a stain

on a fireproof mattress

on the tiled floor of cell no. 5

shackles on arms and feet – nose bone fractured

SUICIDE! officials say

obstinate in their refusal to investigate

the possibility and much more

plausible explanation

of him gotten struck

by lightening

The case is well known among Black Germans and people of African descent living in Germany: the irony used in the poem is not lost us. However, the name “Oury Jalloh” is barely known in Germany outside of these communities. Spoken word artists connect with their audiences directly and emotionally: Koepsell uses a range of tone, voice, volume and movement to perform this poem. It is a critical comment on white German society. It is an articulation of the Black community’s collective pain. How could performances of this poem transform society, inform artistic expression as a whole and reform the way we all communicate about political issues in this country? The possibilities are endless.

In the new scenario, where Black artists, artists of Color and white artists and all have visible equal access to the structures and resources in the German art industry, political correctness no longer becomes a strait jacket which forces cultural producers to sacrifice their artistic freedom for the moral goal of inclusion and self-representation, but it becomes a set of wings: it sets artists free. What will it take for us to usher in this new art industry?

Sharon Dodua Otoo is a Black British mother, activist, author and editor of the book series Witnessed. Her most recent publication is The Little Book of Big Visions. How to be an Artist and Revolutionise the World co-edited by curator and conceptual artist Sandrine Micossé-Aikins (edition assemblage, 2012).

Notes

[1] Where it refers to people, the word “Black” is written with a capital “B” in order to make it clear that it is the political self-definition and social construct which is being referred to. The word “white” as a socio-political category is written in italics, but simply left in small case as it does not incorporate the resistance potential that “Black” does (see Eggers et al 2005:13).

[2] Extract from künstlerische freiheit, a poem by May Ayim (1995) translation: “…taking all words into their mouths / regardless of where they come from / and letting them fall wherever / no matter who they hit…”

[3] In January 2013 Denis Scheck, a German literary critic and journalist, appeared on the German publically funded television channel ARD in blackface, white gloves accompanied by music reminiscent of black and white minstrel shows.

[4] Source: http://www.mirandakaufmann.com/courts.html (last accessed 01.02.13)

[5] “Defending Dessau” reprinted with kind permission from Philipp Khabo Koepsell

References

Ajalon, J. (2012) “THE FUGITIVE ARCHETYPE OF RESISTANCE: A Metamorphical Narrative” in: Micossé-Aikins, S. and Otoo, S.D. (eds.) The Little Book of Big Visions. How to be an Artist and Revolutionize the World (Münster: edition assemblage),pp118-138

Barrett, S.E. (2012) “Creating Space for Evolution” in: Micossé-Aikins, S. and Otoo, S.D. (eds.) The Little Book of Big Visions. How to be an Artist and Revolutionize the World (Münster: edition assemblage), pp139-152

hooks, b. (1999) Talking Back. Thinking Feminist, Thinking Black (Boston, Mass.: South End Press)

Eggers, M.M. et al (Hrsg.) (2005) Mythen, Masken und Subjekte. Kritische Weißseinsforschung in Deutschland (Münster: UNRAST-Verlag)

Köpsell, Philipp Khabo (2010) Die Akte James Knopf. Afrodeutsche Wort- und Streitkunst (Münster: UNRAST-Verlag)

Micossé-Aikins, S. and Otoo, S.D. (2012) The Little Book of Big Visions. How to be an Artist and Revolutionize the World (Münster: edition assemblage)

Mutumba, Y. (2012) “Artists of African Descent in Germany” in: Micossé-Aikins, S. and Otoo, S.D. (eds.) The Little Book of Big Visions. How to be an Artist and Revolutionize the World (Münster: edition assemblage), pp15-31

Otoo, S.D. (2012) “Reclaiming Innocence: Unmasking Representations of Whiteness in German Theatre” in: Micossé-Aikins, S. and Otoo, S.D. (eds.) The Little Book of Big Visions. How to be an Artist and Revolutionize the World (Münster: edition assemblage), pp54-70